With this year’s publication of “British Craneflies” by Alan Stubbs1, it is an opportune time to review the cranefly fauna of Northants, such as we know it, and to encourage more naturalists to start recording these insects. The Cranefly Recording Scheme covers six families of flies. Four families make up the true craneflies in the superfamily Tipuloidea. These are the Tipulidae (Long-palped Craneflies), Cylindrotomidae (Damsel Craneflies), Pediciidae (Hairy-eyed Craneflies) and Limoniidae (Short-palped Craneflies). In addition to these four families two other families are considered “honorary” craneflies: Trichoceridae (Winter Gnats) and Ptychopteridae (Fold-winged Craneflies). In total these families comprise about 350 species in the UK, of which about a third have been recorded in Northants.

Many craneflies have fairly specific habitat requirements in the larval stage and so can be good indicators for assessment of areas for conservation purposes. Some breed in dead wood and are associated with continuity of mature woodland. Many old deer parks as well as woods contain ancient trees and may have interesting craneflies present. Another suite of species are associated with damp soils, some with basic conditions and others with acidic conditions. In general craneflies do best in warm, damp conditions but there are species associated with uplands or which fly in the cooler months of the year. Indeed most Winter Gnats, as their name suggests, fly in sunny weather in the Winter months. A few craneflies have aquatic larvae but most prefer damp soils or leaf litter, damp mosses or damp wood in which to breed. Wet flushes and trickles down rock faces can produce some unusual species. There are species, however, which occur in drier areas, usually in Spring before the summer sun fully dries out the ground.

The adult cranefly season really gets going when hawthorn starts to flower but there will be some species out before that. The season usually ends in late Autumn depending on local weather conditions. Indeed craneflies can make up a significant part of the Autumn diptera fauna. Many species have specific flight periods but some may have more than one peak in the year. Craneflies usually avoid hot sun so in these conditions it is best to seek out shady areas, especially if the ground remains damp. Mossy woodlands and shaded stream banks can be very productive areas. Many craneflies fly at dusk and at night and can be attracted to moth traps so moth trappers can make a big contribution to our knowledge of the distribution of species. Indeed, the Pitsford Water moth traps have yielded a few county firsts since we started recording the by-catch.

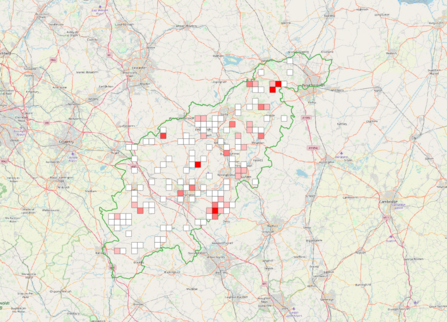

The county species database contains records of craneflies going back just over 20 years but regular recording has only taken place for about 10 years. The attached map shows the distribution of species diversity in the county. There is clearly a need for a lot more recording before we have a good picture of our cranefly fauna. Much of the county has no records and most of the rest has relatively few records, mainly of common species. The data shows that the ancient woodlands, including parkland, and our wetlands are most productive. However this could be down to recorder bias as these are the areas that are most visited. There is great scope for recorders to start to fill in the blanks. As with many other taxa the south-west of the county is under-recorded.