I’ve worked for the Wildlife Trust for over 20 years, and have volunteered in conservation for over 40. In the 1990s we recognised that the status quo wasn’t working for wildlife. Small, isolated nature reserves, however well managed, could not stem the losses caused by modern farming, development pressure and increasingly, dangerous climate change.

Bigger, better, joined up

So, in 2000, we launched Living Landscapes, with the message ‘bigger, better, joined up’ and set about expanding nature reserves and linking them together. We’ve had some big successes - dozens of new nature reserves, and some of them, like the Great Fen and the Nene Wetlands, are huge.

I wish I could say that since then we’d turned the corner, nature was safe and thriving. But last year’s State of Nature Report confirms what I know as a naturalist – species are disappearing, the abundance of nature is dropping fast, 41% of species are still declining and 15% are threatened with extinction.

Over 60 years of the Wildlife Trust responding to threats has not worked. Yes, we’ve had local successes – preventing house-building next to Flitwick Moor, finally defeating plans for a major road through the Ouse Valley meadows (and our reserve at Godmanchester). But old, bad plans for development in the wrong place keep coming back – we need to win every time; a developer needs only win once and a site has gone forever.

Better wildlife law

Since the start of the Wildlife Trust movement (as the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves), we’ve realised that we needed the law on our side. Our founders were instrumental in the first major wildlife laws, in 1949, creating Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), National Nature Reserves (NNRs) and National Parks. The Trusts campaigned for stronger protection for SSSIs, and it eventually came in the Countryside and Rights of Way Act (2000). We were also behind the Marine and Coastal Access Act (2009) which saw the creation of marine protected areas.

But all of this, vital work though it is, is about protecting what species and habitats have survived. As we saw in the 1990s, central England has lost too much already for that to be enough. We have less than half the national average of land protected for wildlife (4% SSSI compared with national 8%, and a county like Cumbria with 17%). We need more land for wildlife.

The new Environment Bill

The Environment Bill currently going through parliament includes two things that could make a big difference: plans for a Nature Recovery Network and a new concept in law, and ‘biodiversity net gain’ (see below for a jargon buster). This means that developers would have to do more than make up for any damage that they do to wildlife.

Let’s be clear, though: some habitats just can’t be replaced. It’s a dangerous falsehood to talk about replacing ancient woodland (as HS2 is currently pretending to do). It’s equally impossible to replace or to move ancient meadows, fens, chalk grassland or chalk streams. These are wildlife’s equivalent of Kings College Chapel or Stonehenge: they must be protected where they are. Most developers know they can no longer destroy Scheduled Ancient Monuments or Listed Buildings. Most have stopped targeting SSSIs. Most try to avoid Local Wildlife Sites. However, we need the law to enforce that: the best places for wildlife must be protected. If properly implemented, biodiversity net gain would make the destruction of any irreplaceable habitat so prohibitively expensive that it will not happen.

But protecting the ‘best bits’ for wildlife is not enough. Every large development damages wildlife. Even the most badly flailed hedgerow or over-mown road verge supports wildlife, and in a large development where more of these habitats are lost under concrete, this adds up to serious impacts. The draft Environment Bill says all this must be replaced, with an additional 10% ‘net gain’. That figure is too low – I’d argue 10% is within the measuring error of ecologists, and we need at least 20% to be sure we’re on the right side. We are campaigning to ensure this increase is reflected in the Environment Bill, and we will also press each local authority to adopt a higher figure even if the government does not change the Bill.

Cynics may say we’re giving in: but there’s living proof in places like Cambourne, Trumpington Meadows and Lilbourne Meadows. Here, there’s far more wildlife after building houses and warehouses than there was before. This Trust has worked since the late 1990s to make Cambourne as good as it can be for wildlife. And it’s not just common species: water voles, scarce plants like slender tare and broad-leaved spurge, rare elm trees, even the occasional breeding black-necked grebe.

Is there space for more development?

Combine a Nature Recovery Network and ‘biodiversity net gain’, and you have the potential to turn things around – but one thing is still missing. Can the area actually cope with more development? Many local residents would say no. I’d say, 'maybe, if…':

If it’s carbon neutral (the climate crisis is going to be far worse than Covid-19 and we can’t carry on as normal); if its demands for water can be met without more abstraction from local aquifers; and if it avoids existing important wildlife habitat, then it may be reasonable to consider it

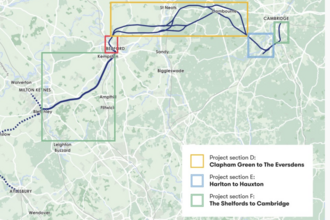

So, a nationally-imposed target of ‘one million more houses’ is wrong. Until you assess the capacity of the area (which hasn't yet been done by any of the proponents of the Oxford-Cambridge Arc), you don’t know if the maximum the area can support is a million, 300,000 or zero. And major new roads, such as the Oxford-Cambridge expressway, are not part of the answer in terms of climate breakdown. That’s why this Trust, working with our neighbours Berks, Bucks & Oxon Wildlife Trust (BBOWT), have campaigned consistently against the expressway, and even took it to judicial review last year.

In case there’s any doubt, we still oppose the expressway. We would like to see an Oxford-Cambridge railway, but only on a route which avoids serious damage to wildlife.

A future with more wildlife

A new approach, of much stronger protection for the most important wildlife habitats, joining them together with a Nature Recovery Network, and making developers pay for any damage they cause to wildlife, has the potential to restore habitats and species, and bring back the abundance of wildlife that we’ve lost in the last century and more.

To give people an idea of what that might look like, we’ve produced a worked example and a set of principles for the Oxford-Cambridge area. It will only work if local people support it, and if government, national and local, deliver on their promises.