The area between Oxford and Cambridge has been identified as the location for one and a half million new homes, new road and rail links, and new places to work.

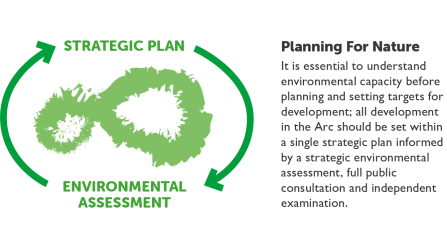

The proposals for this Oxford to Cambridge Growth Arc, as they are currently being planned and delivered, simply won't work. Without proper assessment, government cannot know whether the area could support the current proposals and stay within environmental limits for nature, carbon and water.

The current planning system does not address the needs of society when dealing with development on such a large scale. Today’s climate emergency and extinction crisis require different thinking when it comes to planning and placemaking. We want to see a strategic plan for the whole of the Oxford to Cambridge Arc instead of the current piecemeal approach. Managing water stress, transport pressures, housing requirements, climate obligations, and the need for nature’s recovery can be done in such a way that people benefit from a thriving natural environment which supports healthy lifestyles.

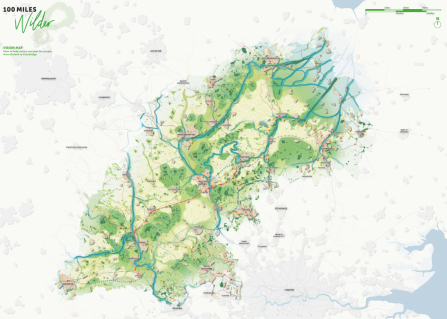

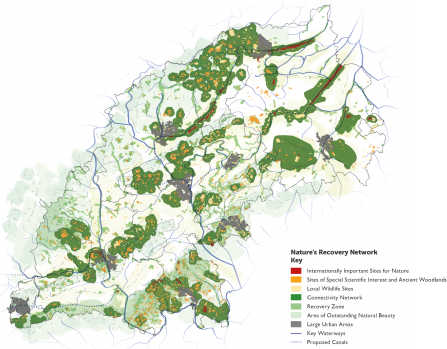

Our alternative vision for the area is for 100 miles of wilder landscape in which to live, work or visit. Our vision map below demonstrates a new way of thinking about how places should be planned: with nature and people’s wellbeing at the centre. This is a solution fit for the 21st century.

Our map focuses on the Oxford-Cambridge area, but the principles and design ideas can be utilised across the UK.

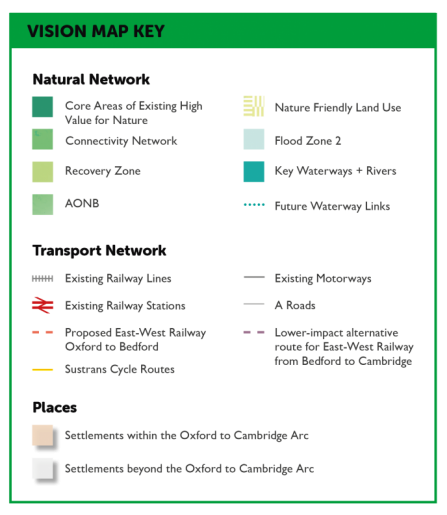

Our Vision Map

This is our vision for helping nature and planning for people, from Oxford to Cambridge. The map highlights the areas of high value for nature and the living networks for wildlife and people. Click on the map for a larger version, or scroll down to learn more about the process of creating our vision.

Living networks for nature

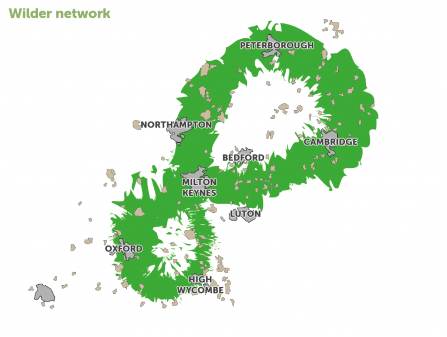

Wilder Network

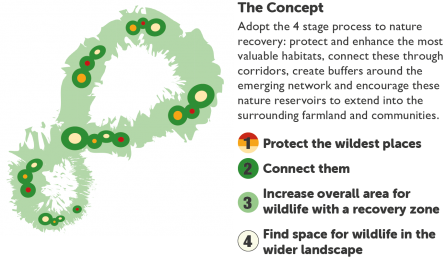

The wilder network is a big, bold plan to protect the wildest places, connect them together and increase the overall area available to wildlife, creating a living legacy for generations to come.

It is a pioneering vision to establish a network where nature can recover and wildlife can thrive.

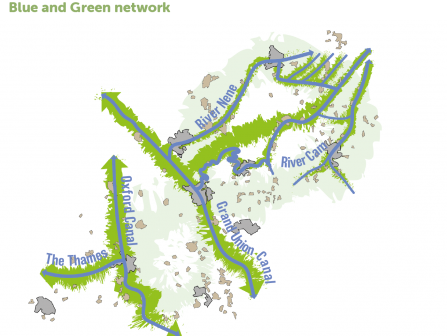

Blue and Green Network

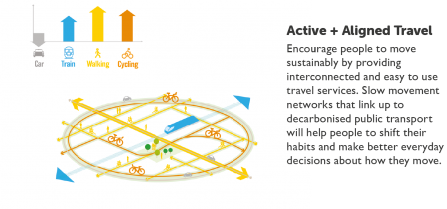

The natural blue and green network connects people to nature; encouraging people to move sustainably by providing access to settlements and wild areas along new and enhanced pedestrian, cycle and boating connections.

Natural corridors allow wildlife to move and migrate freely across the region, linking natural habitats along vibrant green corridors and restored blue waterways.

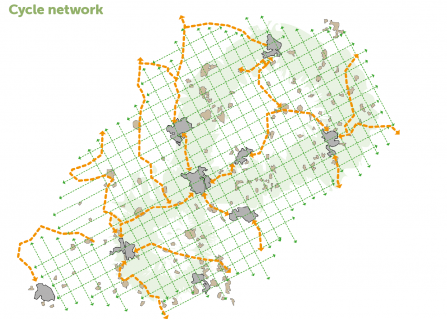

Cycle Network

A concept for a better, more permeable cycle network, strengthening the existing national routes with a 'green grid' of new walking + cycling paths, allowing people to navigate the landscape and encouraging sustainable, slow movement.

Railway Network

The east-west rail is a major opportunity to change the way people move across the region, as the railway network expands away from the London-centric model. Consideration of sustainable transport options will be important in informing the most sustainable locations for development.

The need for a new approach

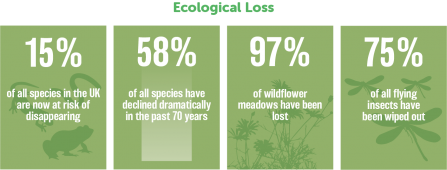

The present crisis for nature in the UK

The hard truth

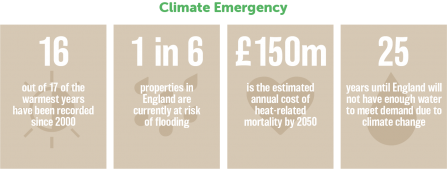

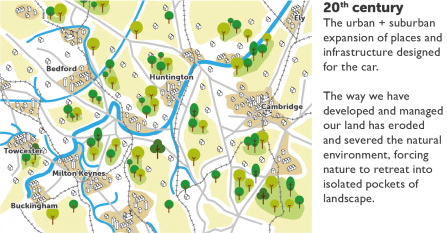

We are facing a climate emergency and ecological crisis. Habitat loss has unintended consequences. These include soil erosion, loss of pollination services, increased risk of flooding, and pollution of water courses. Once environmental degradation begins it is difficult to reverse. At the same time, cities and urban expansion place pressure on natural resources. The Southeast of the UK for example has extremely high levels of water stress.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that global temperatures will increase by 1.5°C by 2050 and will continue to cause longterm changes to the climate, resulting in sea-level rises and increasing the risks of drought, floods, and extreme heat. This will exacerbate the current environmental and biodiversity crises, and affect our way of life.

The need for housing

Addressing the lack of affordable housing is a Government priority. Some assessments suggest that 4 million homes are required to meet our national housing need. We need new homes that cater for a range of needs. But if we do not change the way in which we plan and deliver different types of infrastructure, we will see an acceleration of species loss, with knock-on consequences for our own health, wellbeing and social and environmental sustainability.

If we continue to build in the same way, we will get the same results: increased congestion, pollution and continued deterioration in quality of life. The economic cost of this will be felt from increased social care requirements to the impacts of flooding and a fall in agricultural productivity.

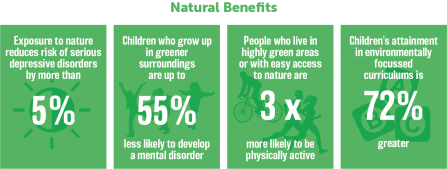

We can decide the future we want to create. We can redesign how we live and work. We can put nature first and reconnect with our wildlife. We can create communities that support healthy lifestyles. We can take advantage of innovation to create new ways of connecting and sustaining communities. By rediscovering the value of nature and enabling communities to reconnect with wildlife and each other, we can capture the full social and environmental value of this approach.

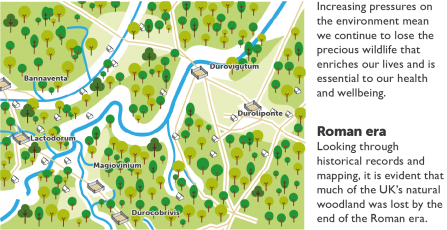

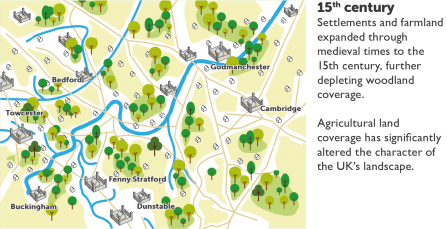

Our history of decline

What does nature need?

Nature's Recovery Network

This is a joined-up system of places important for wildlife; an ambitious network that eventually re-connects our fragmented nature. This network is a key part of our vision for a landscape where wildlife is abundant, development is green, cities are wilder, the countryside is buzzing, soils are healthy and water is plentiful and clean.

The map below shows the area affected by the current proposals for development, from Oxford in the west to Cambridge in the east. The Connectivity Network and Recovery Zones show opportunity areas where nature can most easily spread to newly created habitats. The aim is for a high proportion of land in these zones to contribute to Nature's Recovery Network.

Outside the network must be nature friendly. All land use should include sustainable practices and features that provide habitat for wildlife.

A landscape-led approach

Taking a landscape-led approach means understanding and prioritising nature's needs first.

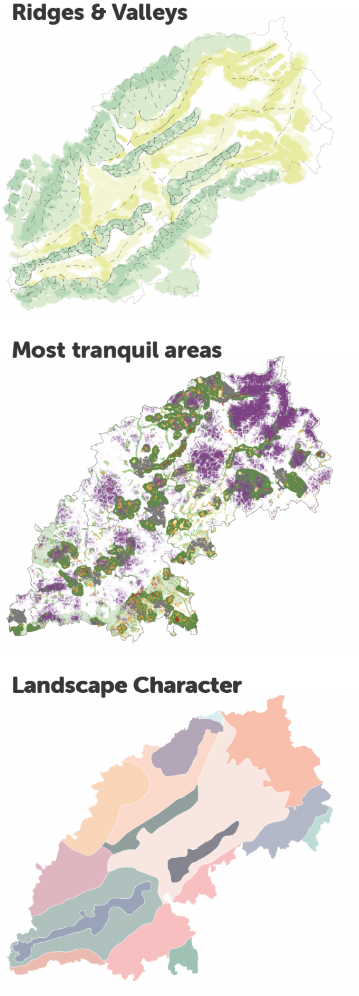

The region's geography is defined by ridges and valleys, structuring the area along corridors that run from the southwest to the northeast.

Interspersed with remnant forests, meadows, grasslands and fens, the region comprises vaious national landscape character areas that have largely been influenced by human activity and retain little of their original character.

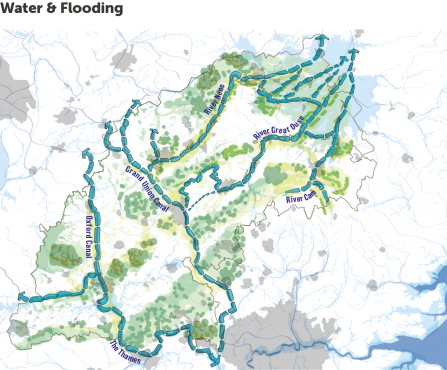

Key waterways include the Thames, River Nene, River Great Ouse and River Cam. Flood mapping reveals the importance of the waterways and fenlands to the northeast of the region, which drain towards the Wash nature reserve on the east coast. Development in these areas could exacerbate flooding issues upstream, and negatively impact the water stress the region is already beginning to experience.

Tranquility data reveals the most tranquil areas across the region, where one can appreciate dark skies and night and quiet retreat in the day.

Nature's Recovery Network has been overlaid with the various geographical constraints and characters, to create a network that will holistically protect, connect and provide room for nature to recover.

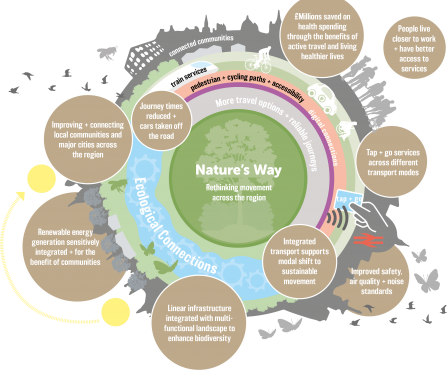

Rethink movement across the region

Our vision includes rethinking the way in which we plan and design movement within the corridor so it is more joined up and takes advantage of the natural landscape.

This means prioritising active travel and planning development that is easily accessible to local services.

We need to change how we plan for new infrastructure, shifting the conversation away from capacity and speed, to redefine the problem we are seeking to solve in the context of social and environmental needs.

Zero Carbon living

How can we do this?

The big benefits

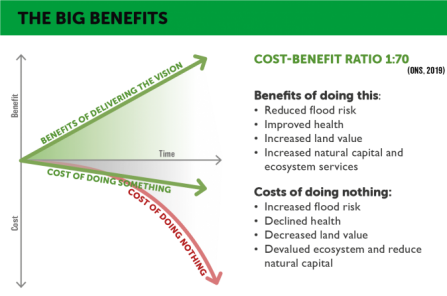

Cost-benefit ratio

The decision to invest in infrastructure is normally based on a comparison of cost to benefit. Whilst we have lots of data to help build cost estimates, historically we have been very poor at understanding the true value of benefits that are difficult to monetise. However, recent advances in evaluating social and environmental value mean that we have more sophisticated tools for considering benefits beyond the red line boundaries of development. This includes consideration of the significant mental and physical health benefits that result from contact with nature and reduced costs of social care. We can also evaluate environmental benefits accruing from increasing natural carbon sinks, reduced flood risk and improved pollinator services. For every £1 invested in natural capital, the ONS estimates a £70 social and environmental benefit.

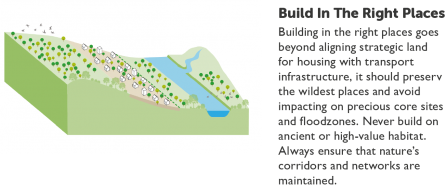

Principles for building nature's way