For some, the idea of cutting trees down to benefit nature is just too much of a contradiction. A few winters ago, whilst doing some woodland management in an ancient woodland, a volunteer watched me fire up my chainsaw and fell an oak that had stood for perhaps eighty years. Barely beyond a sapling in oak years, but to us, it seemed as if it had always been there. The volunteer politely, but clearly in some distress, said, “I don’t know how anyone could cut down an oak tree!” I can understand this perspective.

There’s no denying that trees are wonderful things. They give us accessible oxygen, and many, many other species their homes. They also evoke something emotional in us, and hold important cultural significance too, as symbols of stability, beauty, wisdom and wildness. Is a new roundabout, bypass, or high speed rail link really worth the loss? On the surface, cutting trees down sometimes doesn’t feel quite right. In a landscape (and a world) highly modified by and for humans, our influence is inevitable, and all too often, to the detriment of nature. On our Nature Reserves, we try to make that human influence as positive for wildlife as possible. For conservationists, cutting down a tree is never done without careful thought and the collective application of decades of research. In many cases, cutting some trees down can be hugely beneficial to wildlife.

Nature reserves, strangely, aren’t all that natural. At the Nene Wetlands, the landscape is the product of thousands of years of human influence. Roman settlers favoured the valley to live and farm, as do people today. Until fairly recently, the Nene Wetlands was host to heavy industry, extracting gravel for us to build our infrastructure and homes. And still now, we have an influence. Every person who spends time at a nature reserve will in some way make a difference – we just have to choose what kind of a difference it will be. I think of our nature reserves as natural intensive care units – areas where we intervene heavily to sustain biodiversity, in the hope that one day, our natural residents will be able to redistribute across a healthier countryside. In our nature-poor landscape fragmented by human infrastructure, nature reserves are a last home and last hope for some of our scarcer residents, and an important stop off for many migrants. We therefore need to maximise opportunities for nature to thrive in them, by mimicking natural processes that would have occurred on a much grander scale, many years ago.

Thousands of years ago, our ‘wildwood’ was not just the deep, dark forest of fairy tales – rather a mosaic of wooded and open areas. Trees and tall shrubs would be kept from completely dominating by natural processes like naturally shifting eroding rivers, and consumption and damage of trees by large herbivores such as aurochs, elk and bison. In our modern world of canalised rivers and heavily managed livestock, trees are far more capable of ‘escaping’ natural disturbance than ever before. A landscape of just tall trees would be far poorer in wildlife than one with a mix of habitats, making space for the widest range of species, so in our wooded areas, coppicing is an important part of maintaining this ‘structural mosaic’ of habitats.

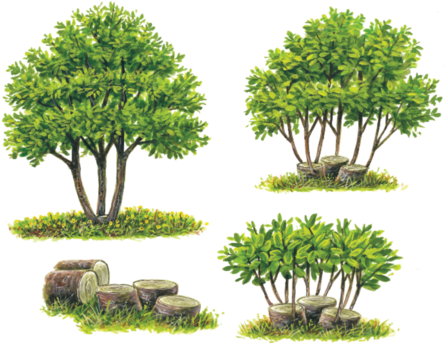

Coppicing is to cut trees close to ground level every few years to allow multiple stems to grow again from the base, or stool. Some tree species do not recover from the process, such as pines, but many will thrive. Perhaps surprisingly, some trees live longer when coppiced than when left alone – a strong indicator that this kind of disturbance is a natural part of the life cycle of many trees. Coppicing is a wonderful process for biodiversity. Among other benefits, letting in warmth and light by removing the tall canopy of trees benefits wildflowers and invertebrates such as butterflies. As the trees grow back, the regrowth of dense, scrubby bushes and trees provides nesting habitat for small birds. As the trees grow taller again, they benefit other species. And so the cycle continues.

Diversity is key, both in terms of ‘biodiversity’ – life in many forms, and structural diversity – physically varied places which mean the widest range of habitat types. By creating structural diversity, we promote biodiversity. Some tall trees that are left to do their own thing are of course welcome too. Large areas of Nene Wetlands are ‘minimal intervention’ – trees away from paths that are left to grow, split, rot and fall over of their own accord. Hole nesting birds like woodpeckers, tawny owls and blue tits like trees like this, as well as bats. Other birds such as herons and cormorants also like tall trees to nest in, as can be seen at Delta Pit. In other areas, no trees are best – specifically where waders may nest or wintering wildfowl like to spend time – for these species, tall trees mean a greater risk of predation. So, across the whole of the nature reserve at the Nene Wetlands, we see the whole spectrum, from wide open grassy areas, to tall trees, to managed coppice, hedgerow and scrub. This structural diversity in turn gives us biodiversity – a nature reserve where as many species as possible can make a home.

From September until March, avoiding the bird nesting season, we cut down trees and scrub to create varied structure, to stop paths closing up and to lessen the likelihood of taller trees falling over and blocking paths. Some trees are laid, rather than cut down completely, but suffice to say for now, a combination of laying and coppicing can be effective. Much of the work at the Nene Wetlands takes place either near water, to benefit, among other things, breeding waders and overwintering wildfowl, or along path edges, though tree works may take place anywhere on the reserve. Paths are where most people will see our work – in years to come the paths will become more and more structurally diverse, and we’ll see more and more benefit to wildlife.